As Just Stop Oil’s protests hit the headlines and Cop27 is dismissed by Greta Thunberg, We hear from campaigners who say disruptive action is necessary to raise the alarm

Naomi Sheena on Killiney Hill. Photo by Gerry Mooney

Tanya Sweeney (Irish Independent)

November 16 2022 11:40 AM

Famous artworks doused in soup. High-end shopfronts defaced. Football matches halted. Traffic brought to a standstill on the busiest motorway. If the goal of Just Stop Oil’s month of protests and civil disobedience was to get people talking about the climate crisis, they can consider it a job well done.

The group’s British arm has since announced that if their demands for change go unmet and Rishi Sunak’s government continues to issue new oil and gas licenses, they will escalate their protests.

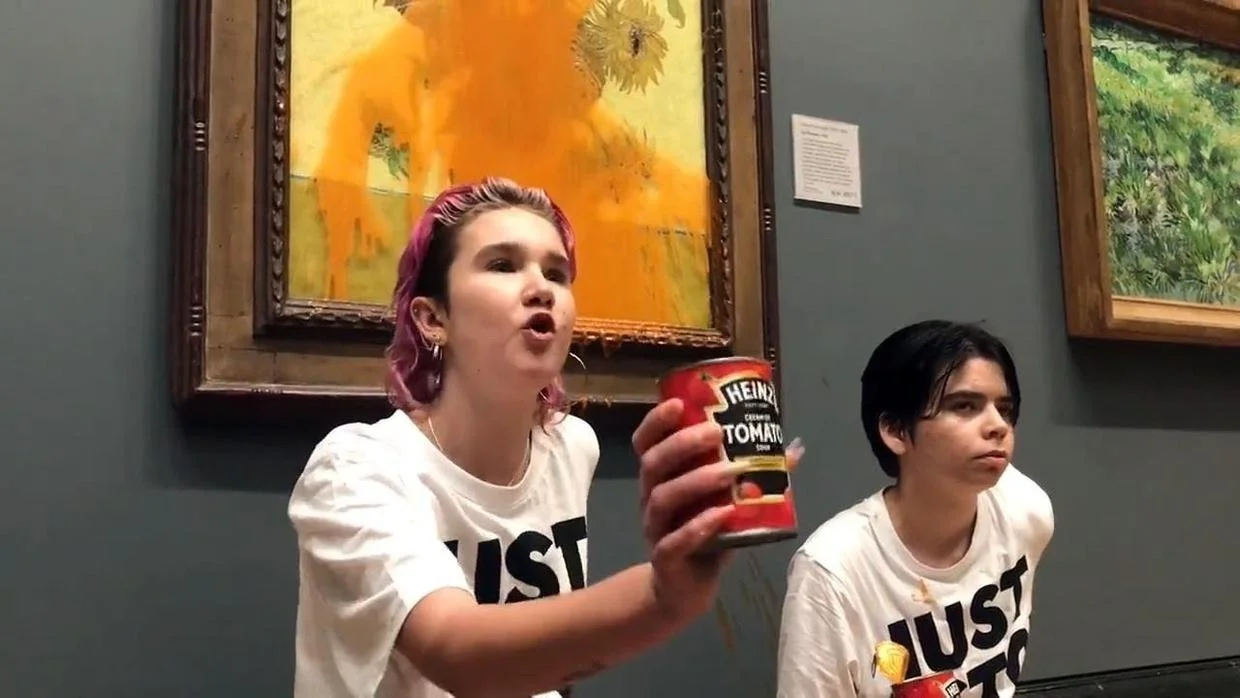

Anna Holland (20) is one of the Just Stop Oil protesters who last month threw soup on Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflowers at the National Gallery in London and glued themselves to the wall beside the painting, which was not damaged. Bob Geldof called the act “clever”. “They’re not killing anyone,” he said.” Climate change will.”

“It’s been really crazy, in a good way,” Holland says of the fallout. “Obviously we received some hate for it, and there’s been controversy. But we knew that it was going to happen.”

Van Gogh stunt: Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland (right) during their Just Stop Oil protest at Britain’s National Gallery. Photo via Getty Images

A recent poll by the Guardian found that 66pc of respondents support civil resistance focusing on climate, but the public response to Just Stop Oil’s protests during October has been divided.

“We take our inspiration from examples in the past — the suffragette movement, the civil rights movement, the queer liberation movements,” Holland says. “They all used non-violent direct action. Even though they were controversial at the time, they worked. They were successful. Now we look back on them as people who broke the system and stood on the right side of history.”

She joined Just Stop Oil after getting frustrated with the lack of progress from conventional protests such as marches and petitions.

“It was like yelling at a brick wall,” she says. “Now, I finally feel like what I’m doing for the climate is making a difference.”

Closer to home, Extinction Rebellion Ireland (XRI) have undertaken protests across the country this year and are pledging to resume civil disobedience in 2023.

In June, XRI protesters took part in a demonstration at Dublin Castle during the National Biodiversity Conference, wearing hard hats and headlamps as part of what they called the “dead canaries in the coalmine” stunt, referencing 30 years of inaction on biodiversity. The protest, they said, led directly to conversations with Malcolm Noonan, the Green minister of state for heritage.

A month earlier, they protested outside the annual meeting of Smurfit Kappa in Dublin, accusing the packaging company of using commercial plantations in Colombia that displace the indigenous Misak people and harm the regional ecosystem. Within weeks, the issue had been raised in the Dáil.

So far, so civilised. What “resuming civil disobedience” might look like for XRI’s Irish activists remains anyone’s guess.

Members of the movement’s Dutch arm and Greenpeace caused disruption at Schiphol airport last week by cycling across the runway and sitting in front of private jets. It might not be far-fetched to predict a similar protest here.

Pedal power: Extinction Rebellion and Greenpeace activists disrupt flights at Schiphol airport in Amsterdam. Photo by Charles M Vella via Getty Images

There is a sense among protesters globally that the time for lip service has long passed. Greta Thunberg is skipping Cop27 in Egypt, describing the climate summit as little more than “an opportunity for leaders and people in power to get attention”.

Such scepticism is not unfounded. One of the main goals of last year’s Cop conference in Glasgow was to stay “within reach” of keeping global warming no higher than 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. Yet the UN’s environment agency reported last month that there was “no credible pathway to 1.5C in place”. Current pledges for action by 2030, if delivered, would mean a rise of about 2.5C and catastrophic extreme weather, it warned.

Against this backdrop, XRI’s climate action campaign co-ordinator Manuel Salazar says its aims are simple: to “raise the alarm”; to challenge government, corporations and employers to take more action to protect the environment.

He admires Just Stop Oil’s month of back-to-back protests in the UK. “I think they have been fantastic, for many reasons,” he says. “They are bringing the conversation back into the media. They’re completely highlighting what is damaging or detrimental to the environment. I think there’s going to be a backlash to that, but at the same time, it will trigger the question of why we are doing this — and how urgent is it.”

He makes an interesting point about the subtext of this civil disobedience: if you think that stopped traffic or a defaced car showroom is an inconvenience, wait until the climate catastrophe really kicks in.

Referring to Holland and her fellow activist Phoebe Plummer’s fateful afternoon in the British National Gallery, he adds: “For people, it’s shocking to see that something we consider a beauty is getting [damaged] but at the same time, they don’t consider that nature has to be protected. People are more worried about something when it’s human-made, as opposed to our own nature.”

The Irish group is unlikely to do something similar, however, he suggests.

“People [in Ireland] don’t like much confrontation in that sense,” he explains. “Instead of blocking roads, we are just going to target those companies or the government or the bodies that are actually creating this crisis.”

Salazar, who works in Dublin as a tech consultant, joined XRI in 2019 and is part of a 500-strong membership that is diverse in age, origin and gender. Originally from Venezuela, he says he was “quite surprised” by the apathy towards the climate crisis in Ireland, both by individuals and government.

‘Surprised’ by Irish apathy: Activist Manuel Salazar. Photo by Steve Humphreys

“I guess there are several reasons for that: climate change hasn’t impacted Ireland so much as other countries, so around eight out of 10 people think that climate change is not affecting them directly, which is worrying,” he says.

“At the same time, 85pc of Irish people think that climate change needs to be addressed. But as long as it’s business as usual, and fires aren’t happening, or flooding is happening in our house, we won’t act on that. And that’s human nature. We are more reactive than proactive.”

Claire (not her real name) is a Dublin-born activist and academic who has sought to analyse the public’s apathy towards climate protesters and the crisis in general. Often, she says, apathy is a defence mechanism, a way to avoid facing up to the gravity of a situation.

“There’s this conception that protesters are in some ways going too far,” she says. “Many people would just prefer that there’s a lane and you stay in it.”

Naomi Sheehan has witnessed first-hand the devastating effects of climate change more than once. In 2019, the Dubliner was caught in the California wildfires, in a horrifying situation where she did not have access to food or water.

Until recently, she lived in Switzerland and witnessed some of the extreme flooding that swept through Europe last summer, which killed at least 243 people. There was also a huge mudslide near her home.

Afterwards, she talked about the mudslide with her nine-year-old godchild and her young friends. “She said, ‘Did you know this was going to happen?’, and I had to say to her, ‘Yes, I knew’,” says Sheehan.

“She looked at me with such hatred. She then said, ‘We need you to be the adults. We’re children. You’re supposed to be protecting us, not the other way around’. They were crying their eyes out because their lives were about to end over this, and that’s not OK.

“It’s why I changed my life. As soon as I knew how bad the climate crisis was, I did everything I could in terms of trying to change things.”

She believes the Irish government is not doing enough to warn the public about the urgency of the crisis.

“They put a load of numbers out there, but a lot of people don’t speak in numbers,” she says. “Now, I ask people, ‘Where are you going to be in 30 years’ time and how old will you be? Because I’ll be 70 and I’m not prepared to fight anybody for food or water, which we will have to do’. And I’ve yet to meet someone who is prepared.”

Sheehan left her well-paid executive role to do a master’s in sustainable development. Now a sustainable development scientist, she is also a member of Scientist Rebellion, an environmentalist group populated mainly by scientists.

Ian Coleman from Wexford joined the group after doing a master’s in bioinformatics at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. He too has been heavily involved in staging protests, including at the World Health Summit in Berlin last month.

“For Scientist Rebellion particularly, I think it’s good to get through to people that this isn’t just a bunch of people you can dismiss as hippies or radicals,” he says. “These are real scientists, getting arrested on the streets because they’re so worried about this.”

Speaking of dismissing activists as radicals, Sheehan says Just Stop Oil’s recent protests have been unfairly maligned.

“There’s a lot of heavy criticism coming in for JSO, and people are saying, ‘This is not the way to do it, you’ve lost me’ kind of thing,” she says. “I’ll be honest, 10 years ago I’d probably have said the same thing. But when you’ve seen the climate collapse events that I’ve witnessed, all you can think of is, ‘I should have been doing way more’.

“If a group of people are being ostracised for trying to save their own lives, as well as yours and mine, well I think we really need to take a look at our collective morals and values.”

It’s not just younger people who are feeling disaffected enough to get out and protest. After retiring, Dubliner Louis Heath joined Extinction Rebellion in 2019. Within a year, he had hit the headlines with a protest at Killiney Bay over rising sea levels, dressing as a ‘sea god’ alongside fellow activist Ceara Carney.

Heath is a vegan and decided some years ago not to take any flights but something bigger started to shift within him in 2018. “I started getting feelings about the urgency of climate, and I think it was the first time I considered extinction as a possibility with climate change,” he says.

Why does he believe that civil disobedience and protests work? “Politicians are vote-orientated,” he says.

“I remember we were chasing Richard Bruton [then minister for the environment] in all the places he was giving speeches and addresses. He was hounded by us. You could see the expression in his face, ‘No, not them again’.

"One time he was coming out of a talk in Malahide and we sat down at the front of the car and back of the car, but we stopped the car from moving. He was so frustrated and he was ranting and raving, and went off to get a taxi. At that time in 2019, it got into the newspapers. That definitely had an impact.”

Louis Heath with his Extinction Rebellion flag: ‘If we were in the UK, I would surely have been arrested several times’. Photo by Mark Condren

Heath has also been involved in demonstrations where traffic has been stopped. “We always inform the guards that we’re doing it, because you’re limited to seven minutes — it’s not disrupting traffic too much. We usually have biscuits or buns and we hand them to people and have a leaflet.

"We’d apologise and explain to them we’re in a crisis, and they’re generally fine. You’d meet the odd person in a mad rush, but they’re few and far between, actually. It’s sort of acceptable here. If we were in the UK, I would surely have been arrested several times.”

Heath says that stopping public transport can run the risk of “alienating” people: his own activism in the future, he says, is likely to involve “getting into more detail and easily digestible ways of bringing the message across in a more informed and detailed way”.

The task of prompting corporations and governments to enact meaningful change continues. Asked what measures individuals can take to make even a small difference in the face of looming catastrophe, Heath says: “People can find carbon footprint calculators online. Friends of the Earth have a good one.

"Firstly, people should be aware of their own carbon footprint and the ways to reduce this. If everyone in Ireland reduced their output by one tonne of CO2, it would reduce Ireland’s total emissions by approximately 12pc. That would make a phenomenal difference.”

Coleman of Scientist Rebellion suggest emailing TDs to ask: “Are we still subsidising fossil fuels years after Ireland has declared a climate emergency? And if so, can we move that subsidy into some other way to make people’s lives easier, without funding the murder of our youth and the next generations?”

He adds: “There is so much despair around this [issue] and if you look at the scientific literature on the psychology of all of this, it’s really devastating. The burnout rates in activism are so high, but then, when people actually participate and get on the streets, it sort of lifts the despair a bit.”